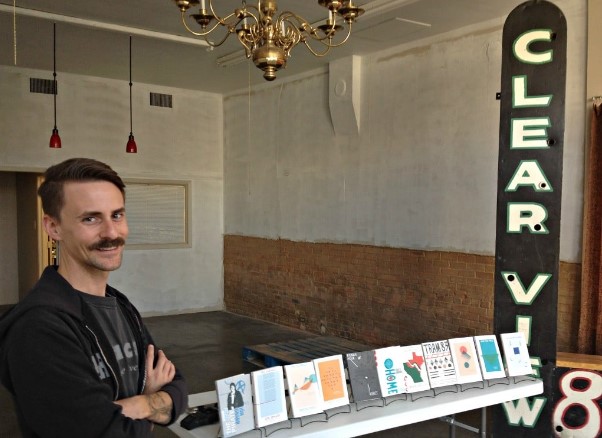

Will Evans, owner of Deep Vellum Press, said he knew there was a possibility he might eventually be honored by France. After all, he currently peddles more English translations of French books than any other publisher.

Monday, Evans will be thanked for his efforts spreading French literature by offically becoming a Chevalier (that is, a knight) of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres with a medal presented by the new cultural counselor of France, Mohamed Bouabdallah. This will be the counselor’s first visit to Dallas.

Still something of an upstart at 11 years old, Deep Vellum Press acquired the assets of the venerable Dalkey Archive Press in 2020 after its founder John O’Brien died. Since 1984, Dalkey Archive had been dedicated to recovering works that had fallen out of print — in particular, works in translation. It published more than 1,000 books from 50 different languages, including works by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Carlos Fuentes and Gertrude Stein.

O’Brien himself had been appointed a Chevalier by the French — which is why, Evans explained, he had an inkling the honor might be coming his way as well.

When Deep Vellum acquired the Dalkey Archive, Evans said, “I made an offhand joke to some of our colleagues, that, at the time, the ambassador of France to Ireland said that Dalkey Archive Press had more books translated from French than any other publisher in the history of the English language. And I said, ‘Well, by gosh, that now makes me the biggest publisher of translations of French in the history of the English language.'”

“But it still came as quite a surprise,” he said of the French honor. “I almost fell out of my chair.”

For the record, Evans said that across his different imprints, he currently publishes more than 160 French translations.

Evans came to Dallas and started Deep Vellum in 2013, which released its first five titles the next year. The company name, a play on Deep Ellum, refers to vellum, another term for parchment, which was made from animal skins and was used to make books before paper was invented.

Only 3% of book sales

Of those first five books from Deep Vellum, one was in French: Anne Garetta’s 1986 novel, Sphinx — which, Evans said, turned out to be their first hit and remains one of the company’s bestsellers.

When Deep Vellum acquires other publishers, like Dalkey, it acquires their ‘backlist’ – that is, books that have already been published. Otherwise, it publishes North Texas authors, including historian Alan Govenar and journalist Jim Schutze.

But it mostly publishes translations, which typically don’t sell well in America. The University of Rochester has a website devoted to translations called Three Percent. That’s the traditional percentage of American book sales that translations make up. And Deep Vellum doesn’t publish translations solely from widely-spoken Western languages like French or German but also Macedonian, Kurdish and Mongolian.

Evans said that acquiring backlists from other publishers makes sense because “actually, backlist sells more than frontlist.”

As for the paltry sales of translations, he noted that Deep Vellum was deliberately set up as a non-profit.

“It’s not just that translations don’t sell,” he said, “it’s that the entire commercial publishing landscape comes out of New York City from five companies.”

The “Big Five” trade publishers are Penguin Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster.

As a result, Evans said, translations are neglected, as well as “books by authors from places like Dallas, and more importantly, that means that they’ve neglected readers. And they’ve said that we don’t deserve stories from French writers or writers from Kurdistan. We don’t deserve to read Jonathan Norton of Pleasant Grove or Jon Fosse of Norway — two authors, one is from our backyard, one is from the fjords of Norway. [Fosse] won the Nobel Prize in October, and Jonathan is now the interim artistic director at the Dallas Theater Center.”

Evans added, the two are “both playwrights, both amazing.”

International and independent

The New York Times recently ran a feature about Deep Vellum Press and the Oak Cliff bookstore, the Wild Detectives. The Times cited these as evidence that Dallas had elements of an international and independent literary scene.

But both Deep Vellum and the Wild Detectives started around 11 years ago. So what has changed since then?

“The New York Times article is a beautiful piece of external validation,” Evans said. “And I’m one of the luckiest people in the world that when I moved here, Javier Garcia del Moral and Paco Vique were opening the Wild Detectives with a very similar mindset and vision about how Dallas is a part of the world and how we could bring the world here.”

Evans said his own bookstore, Deep Vellum on Commerce Street in Deep Ellum, was modeled on the Wild Detectives.

What’s changed since then, he said, “is that it’s not just Wild Detectives now. Around the corner, there’s Whose Books and around the corner from that, Poet’s Bookshop. Look at the Pan-African Connection. Look at Interabang Books, which is doing so much work with international culture, starting literary prizes and podcasts.”

Add the translation studies program at the University of Texas at Dallas, the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture and the publication, the Southwest Review, at Southern Methodist University — “and it’s all those pieces,” Evans said. “You have to connect the dots between them, the same way that when you look at the stars in the sky, you have to draw the lines between the stars to actually make a constellation appear.”

Ultimately, Evans said, “it’s that the community of Dallasites and North Texans are looking for this kind of experience – they’re starving for books. They’re starving for intellectual stimulation.”